Volume 8 - Year 2025- Pages 187-197

DOI: 10.11159/ijci.2025.019

Investigating the Workability and Mechanical Properties of Fly Ash-Glass Waste Geopolymer Concrete with Recycled Steel Can Fibers

Louis M. Wong IV1, David Andrew M. Balingit1, Michael Joshua B. Espiritu1, Edgardo S. Cruz1

1Mapúa University

658 Muralla St, Intramuros, Manila, 1002 Metro Manila, Philippines

limwong@mymail.mapua.edu.ph, dambalingit@mymail.mapua.edu.ph,

mjbespiritu@mymail.mapua.edu.ph, escruz@mapua.edu.ph

Abstract - Concrete plays a vital role in civil engineering and infrastructure development. As the focus shifts toward sustainable practices, innovative approaches such as geopolymer concrete and the use of glass waste as aggregates have emerged, improving both the environmental impact of concrete and its mechanical properties. Fiber reinforcement, especially with recycled materials, has gained attention for enhancing the sustainability of concrete, with commercial storage materials such as steel cans becoming viable reinforcement. This study examined the workability, compressive strength, and tensile strength of fly ash–glass waste fiber-reinforced geopolymer concrete (FRGC) using recycled steel can fibers. Samples were produced by crushing soda-lime glass bottles and cutting steel cans into hook-end fibers, with an M20 concrete mix formulated by substituting 30% of cement with fly ash and 30% of coarse aggregate with glass waste. Recycled steel can fibers were added at varying percentages (0–5% by weight of cement). Results showed a decrease in workability as recycled fibers were added. Although compressive strength also decreased, the reduction was insignificant at 4% fiber content. The addition of fibers improved tensile performance, though the increase remained statistically insignificant compared to the control group. Notably, concrete samples containing recycled steel can fibers exhibited ductile failure and fiber bridging. Overall, the fly ash–glass waste FRGC with 4% recycled steel can fibers demonstrated favorable outcomes in compressive and tensile strengths. This study highlights the potential of using recycled steel cans to enhance concrete sustainability.

Keywords: Fiber-Reinforced Concrete (FRC), Geopolymer Concrete, Recycled Fibers, Workability, Compressive Strength, Tensile Strength

© Copyright 2025 Authors - This is an Open Access article published under the Creative Commons Attribution License terms. Unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Date Received: 2025-03-24

Date Revised: 2025-08-27

Date Accepted: 2025-09-30

Date Published: 2025-12-01

1. Introduction

Among many innovations in civil engineering, concrete remains a constant element for creating different structures. Its long lifespan, high compressive strength, and ability to withstand heat and fire make it valuable in construction [1]. It can withstand tensile stress upon pairing with reinforcements such as steel bars, making reinforced concrete a reliable building material that offers durability, strength, versatility, and cost-effectiveness. As a result, reinforced concrete is commonly applied to existing buildings and infrastructures such as bridges, flyovers, roads, and marine structures [2]. While Ordinary Portland Cement is the standard choice for concrete, experts remain open to choices regarding economy, design, and the recent promotion of sustainable practices, with Geopolymer concrete consequently becoming a significant interest in the civil engineering industry.

Geopolymer concrete is a special type of concrete made by combining aluminate and silicate-bearing materials through a caustic activator [3]. After several studies exploring its mechanics and potential applications, engineers began to incorporate geopolymer concrete into practice, as it outperforms OPC in several aspects. According to Madhavi [4], one of the benefits of geopolymer concrete is its substantially lower carbon dioxide emissions, a significant issue in the production of OPC, along with its demonstrable increase in strength and workability. Furthermore, unlike OPC, which consumes large amounts of natural resources, geopolymer concrete makes use of organic materials or industrial waste. As concrete became more widely used in the industry, studies were conducted regarding innovations. Glass waste is another concrete component that can be utilized as aggregates in concrete. These glass wastes usually come from beverage bottles that are made up of soda-lime glass. According to Afshinnia [5], glass waste can become compatible with concrete when partnered with fly ash, another sustainable material in concrete mixtures. In addition, glass waste is known to provide better abrasion resistance than mineral aggregates.

These innovations in the industry have demonstrated the growing consideration of sustainability and environmentally friendly alternatives for materials used in building infrastructure and other types of structures through the use of recyclable materials and renewable resources [6]. As stated earlier, with examples such as geopolymer concrete and glass waste, the sustainability of concrete mix production is highly evident. In line with sustainable practices in producing concrete mixes, alternatives for concrete reinforcement have also been explored. One such innovation is fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC), which utilizes thin fibers in the mix to reduce shrinkage-induced cracks, increase strength, and enhance stress distribution within the concrete [7]. Furthermore, one of the more commonly used fibers in several studies is steel fiber, which is the type of reinforcement this study focuses on. Steel fibers are strips of steel with specific lengths and diameters, randomly distributed throughout the concrete mix. These fibers have various configurations that differ in shape, size, and other mechanical properties, all of which provide significant improvements in concrete performance. The development of fiber-reinforced concrete also introduced more sustainable options, such as the use of recyclable fibers.

The use of recycled fibers in FRC has been a topic of interest for years, with researchers and scholars seeking ways to reuse waste products in the construction industry. Steel cans are among the most common household materials, used as containers for food, oil, chemicals, and other products. They are considered 100% recyclable due to their composition. Steel cans are often confused with tin or aluminum cans because of their similar functions and physical properties [8]. However, steel cans are typically food containers made primarily of steel, with tin serving only as a coating [9]. This means that steel cans primarily retain the mechanical properties of steel rather than tin. In addition, they differ from beverage cans, which are commonly made of either aluminum or tin. The relevance of using steel cans in construction arises from their favorable mechanical properties, which include axial resistance (resistance to loads), radial resistance (resistance to external pressure), and resistance to deformation due to internal pressure [10]. Moreover, aside from being highly resistant to applied forces, steel’s malleability and plasticity make steel cans suitable for recycling and repurposing [11]. Their mechanical properties, combined with their recyclability, render them economical and environmentally friendly materials with strong potential as fiber reinforcement.

Using steel cans to produce recycled fibers, and combining them with other sustainable innovations such as fly ash geopolymer concrete and glass waste, can result in significantly more eco-friendly concrete. While the individual benefits of geopolymer concrete, glass waste, and recycled steel can fibers are already recognized, there remains a need for empirical knowledge on how these materials, when combined, affect the performance of concrete. With this in mind, the objective of this study is to assess the workability, compressive strength, and tensile strength of fly ash–glass waste fiber-reinforced geopolymer concrete (FRGC) with recycled steel can fibers. This study also aims to evaluate the viability of using recycled steel can fibers to contribute to the development of more environmentally friendly concrete for various construction purposes.

2. Related Works

2.1. Fiber Reinforced Concrete

Anas et al. [12] reviewed the application of FRC in the construction industry. The study highlighted various synthetic and natural fibers used to improve concrete properties. Steel fibers have been shown to increase compressive, flexural, and tensile strength, while also improving concrete’s ductility, crack resistance, impact resistance, abrasion resistance, and energy absorption. A significant increase in compressive strength was recorded at a 3% fiber–cement ratio. However, higher fiber content in the concrete matrix reduces workability, though this issue can be mitigated with the use of superplasticizers.

In assessing the effect of steel fiber addition on concrete, Joshi et al. [13] examined the tensile, shear, flexural, and compressive strengths of reinforced concrete. Additionally, reserve strength and cracking behavior were analyzed. Steel fibers with an aspect ratio of 50 were used in OPC grades M20, M25, M30, and M40. The study’s findings indicated that the percentage increase in compressive, tensile, and shear strengths was nearly the same across all grades of conventional concrete. The ultimate and reserve strengths of FRC were significantly greater than those of ordinary concrete. As failure became more ductile, the cracking pattern of FRC under compression changed, resulting in greater toughness. This was also emphasized in the work of Jamal [14], which highlighted the changing behavior of concrete from brittleness to ductility as fibers are incorporated. Furthermore, Joshi et al. [13] and Jamal [14] stressed that fiber configuration influences the performance of FRC, as it provides better bond and anchorage to the concrete. Hook-end steel fibers are the most commonly used type, as they improve resistance to pullout compared to straight fibers, which exhibit limited bonding potential.

Alrawashdeh and Eren [15] investigated the mechanical and physical properties of steel fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete (SFR-SCC) using various aspect ratios and volume fractions of hook-end steel fibers. The study found that increasing steel fiber content decreased rheology and workability. Compressive strength initially decreased with higher fiber content, but this reduction lessened at greater fiber ratios. Meanwhile, splitting tensile strength and flexural strength increased with both fiber volume fraction and aspect ratio.

2.2. Recycled Fibers

Akhund [16] explored the use of recycled soft drink can fibers as reinforcement in concrete, focusing on their impact on compressive strength and workability. The study found that increasing the percentage and size of recycled can fibers reduced workability (lower slump values). Conversely, both fiber size and content positively correlated with compressive strength. The FRC mixes exhibited improved compressive strength compared to the control concrete after 28 days.

Sambrano and Estores [17] investigated the effects of incorporating recycled soft drink can fibers on the compressive strength of non-load-bearing concrete hollow blocks (CHBs). The study found a positive correlation between fiber length and content with compressive strength. Control CHBs had a compressive strength of 213.33 psi. The highest compressive strength (495 psi) was achieved with 3% fiber content and 25 mm fiber length, representing a 133.13% increase compared to the controls. Post-cracking analysis revealed failure modes such as shear failure, diagonal cracking, and face shell separation. However, fiber inclusion also improved crack resistance.

Wijatmiko [18] examined the strength properties of soft drink cans used as fiber reinforcement for lightweight concrete. A total of 36 concrete cylinders, each 300 mm in height and 150 mm in diameter, were prepared. The study investigated the effects of two distinct fiber shapes (hooked and clipped) and varying fiber fractions. The findings showed that hooked fibers increased compressive strength by more than 40%, while a 10% increase in fiber content raised tensile strength by 23%. The use of fibers, particularly with an interlocking mechanism, also prevented pumice from floating to the surface and ensured uniform distribution within the concrete.

2.3. Glass Waste Aggregate Concrete

Tamanna [19] investigated soda-lime glass bottles as a substitute for partially replacing coarse and fine aggregates. The study found that utilizing glass waste as coarse aggregate reduced the compressive strength of conventional concrete as the glass content increased. Furthermore, the central issue of alkali–silica reaction (ASR) was observed. ASR occurs between amorphous silica in glass and alkali in cement, producing expansive alkali–silica gel. This gel, when exposed to moisture, absorbs water and expands inside the concrete, causing cracking and reducing service life. However, when glass is used as a partial fine aggregate replacement, the negative effects of ASR are reduced, and a pozzolanic reaction between the glass particles and the calcium hydroxide in cement occurs, resulting in delayed strength gain. Using glass waste in sand form has been shown to be ideal. However, incorporating waste glass sand reduces workability. At 20% replacement, waste glass sand slightly increased compressive, flexural, and tensile properties, but further increases in content led to reductions.

Malik et al. [20] examined waste glass as a potential partial substitute for fine aggregates in M25 concrete, comparing the results to those of conventional concrete after testing for density, durability (water absorption), splitting tensile strength, and compressive strength after 28 days. Several benefits were observed with the incorporation of waste glass. Replacing 20% of the fine aggregate significantly increased compressive strength. Replacement up to 30% still produced a 9.8% increase in 28-day compressive strength. Higher waste glass content also reduced water absorption, improving durability. Moreover, using 40% waste glass reduced concrete’s weight by 5%. Workability also improved with greater waste glass content. However, splitting tensile strength decreased as waste glass content increased, which should be considered when tensile performance is critical.

Adajar et al. [21] assessed the viability of replacing coarse aggregate in fly ash geopolymer concrete with soda-lime glass, with particular attention to the risk of ASR. Their findings indicated that compressive strength was significantly improved by substituting soda-lime glass for up to 30% of the coarse aggregate. Compressive strength was also enhanced by substituting Class F fly ash for up to 30% of cement. An empirical model was developed to predict compressive strength based on soda-lime glass substitution levels. While flexural strength showed a slight, insignificant decrease with higher soda-lime glass content, beams containing soda-lime glass exhibited reduced ductility based on stress–strain behavior. Crucially, incorporating 30% Class F fly ash effectively mitigated ASR, enabling the safe use of 30% soda-lime glass without harmful expansion. These findings demonstrate that soda-lime glass can be used as a coarse aggregate substitute in concrete when paired with moderate volumes of Class F fly ash as an appropriate ASR-mitigating agent.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

To assess the mechanical properties of fly ash–glass waste fiber-reinforced geopolymer concrete (FRGC) with recycled steel can fibers, the researchers conducted an experimental study at the School of Civil, Environmental, and Geological Engineering (SCEGE) Laboratory, Mapúa University, Manila, Philippines.

3. 2. Gathering of Materials

The materials used in producing the geopolymer concrete were ordinary Portland cement (OPC), sand, gravel, Class F fly ash, and glass waste. The OPC, sand, gravel, and fly ash were purchased from a local construction supplier. Meanwhile, soda-lime glass bottles were collected from local junk shops and eateries. The bottles were first crushed for easier transport, then pulverized using a waste shredder at the Manila City Material Recovery Facility to produce the required glass waste (see Figure 1). The resulting glass waste had a grain size similar to fine sand.

3.3. Praparation of Steel Can Fibers

The researchers collected waste cooking oil cans made of steel from restaurants within Metro Manila, Philippines. The collected cans were washed and dried, then transported to a local construction company, Fundamentum Construction, for cutting. Figure 2 shows the recycled steel can fibers produced. A hook-end configuration was used to provide an interlocking mechanism. The thickness of the recycled steel can fibers was 3 mm.

3. 4. Production of Fly Ash-Glass Waste Fiber-Reinforced Geopolymer Concrete

Concrete test cylinders were produced following ASTM C31, with procedures adapted from Adajar et al. [21]. Thirty percent (30%) by weight of cement was replaced with fly ash, while 30% by weight of coarse aggregates was replaced with glass waste. Recycled steel can fibers were added at 0.0%, 1.0%, 2.0%, 3.0%, 4.0%, and 5.0% of the weight of cement, producing six (6) treatment groups. The materials were first mixed until homogeneous, after which water was added at a 0.6 water–cement ratio. The FRGC mix was then poured into PVC cylindrical molds measuring 100 mm in diameter and 200 mm in height. The researchers fabricated the molds in accordance with ASTM C470. The molded specimens were left to dry and cure for 28 days. A total of 36 FRGC samples were produced, with three (3) samples per treatment for compressive strength testing and three (3) for tensile strength testing.

3.5. Workability Test, Compressive Strength Test, and Tensile Strength Test

Before the FRGC mix was poured into the molds, a workability test (slump test) was conducted in accordance with ASTM C143. Compressive strength testing of FRGC samples was performed in accordance with ASTM C39 after the 28-day curing period. Tensile strength was evaluated using the split tensile test in accordance with ASTM C496. A universal testing machine was used for both strength tests, which were conducted after 28 days of curing.

3.6. Data Analysis

The researchers ensured that all concrete tests followed ASTM standards. Data from the compressive and split tensile tests were evaluated according to their respective ASTM standards, with precision and bias checks conducted in accordance with ASTM C670. According to ASTM C39 and ASTM C670, the coefficient of variation of three results in a treatment must not exceed 7.8% under laboratory conditions for compressive strength tests. Similarly, ASTM C496 and ASTM C670 suggest that the coefficient of variation of three results in a treatment should not exceed 16.5% for split tensile tests.

The gathered data were then evaluated using cubic regression. Compressive strength and tensile strength were further analyzed through analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post-hoc tests to determine significant differences between FRGC treatments. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Workability Test

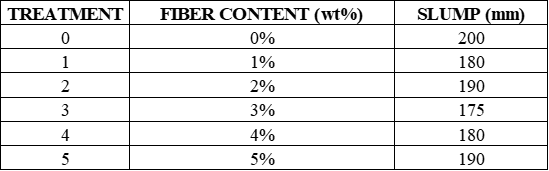

Table 1 presents the slump values recorded per treatment in the workability test for fly ash–glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers. With a water–cement ratio of 0.6, the control group (treatment 0) recorded a slump value of 200 mm, indicating high workability. This high workability may be attributed to the combined presence of fly ash and fine glass waste, both of which are reported to improve workability [5], [20], [22].

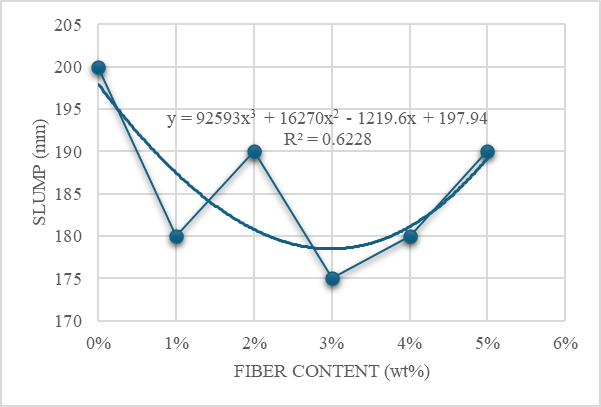

When recycled steel can fibers were added, slump values decreased and fluctuated, as shown in Figure 3. The lowest slump value (175 mm) was observed in treatment 3. The cubic regression, with an R² value of 0.6228, indicates a decreasing trend until treatment 3, followed by an increasing trend through treatment 5. All fiber-reinforced treatments had lower slump values than the control group. This reduction suggests lower workability as fiber content increases, consistent with observations in earlier studies on fiber-reinforced concrete [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [23]. Mishra [23] also highlighted slump reduction as a consideration in FRC design. The fluctuations in slump may have resulted from variations in the quantity and quality of the materials used.

4.2. Compressive Strength Test

Data from the compressive strength test, performed in accordance with ASTM C39, were first evaluated under ASTM C670 requirements. All treatments passed the precision check, as the coefficient of variation for each treatment remained within the 7.8% limit under laboratory conditions.

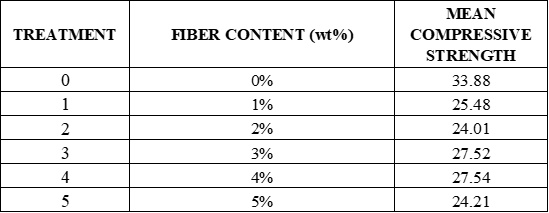

Table 2 summarizes the mean compressive strengths at 28 days. All treatments exceeded the target design strength of 20 MPa. The control group (treatment 0) achieved 33.88 MPa, which is 69.4% higher than the design strength. This result was consistent with Adajar et al. [21], who reported a mean strength of 36.01 MPa (71.5% above their design strength of 21 MPa) for mixes with 30% fly ash and 30% glass waste.

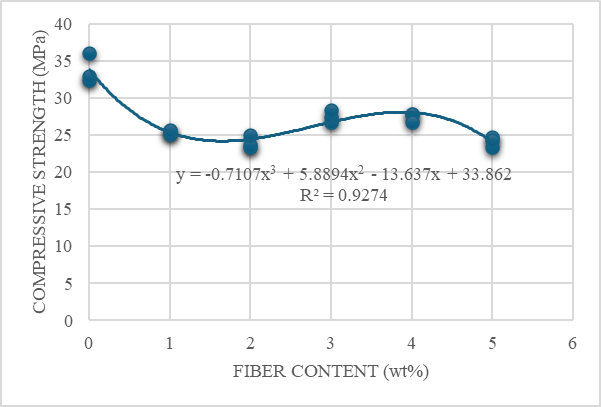

As shown in Figure 4, the cubic regression (R² = 0.9274) revealed an initial decrease in strength with fiber addition. Treatment 2 (2% fiber content) had the lowest mean compressive strength (24.01 MPa). Strength increased again at treatment 4 (4% fiber content), which reached the highest value among fiber-reinforced mixes (27.54 MPa), before decreasing at treatment 5.

(compressive strength test).

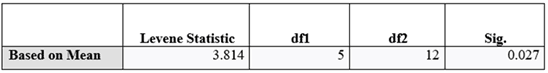

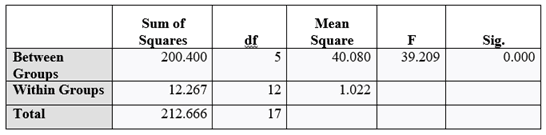

A homogeneity of variance test was conducted to determine whether the variances of the treatments could be assumed equal. Table 3 presents the results, showing a significance value (p = 0.027), which indicates a violation of the homogeneity assumption. Therefore, Welch’s ANOVA was performed alongside the one-way ANOVA.

(compressive strength test).

(compressive strength test).

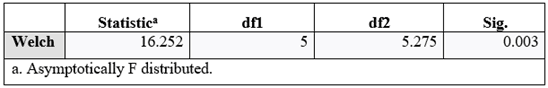

The one-way ANOVA was used to assess whether there were significant differences between the treatments. As shown in Table 4, the p-value was 0.000, below the 0.05 significance level. Similarly, Welch’s ANOVA (Table 5), conducted as a robust test of equality of means, yielded a p-value of 0.003, also below 0.05. These results confirm that there were significant differences in compressive strength among the FRGC treatments with varying fiber content.

A post-hoc Games–Howell test was conducted to determine which specific treatments differed, as this test is appropriate when variances are not homogeneous. The significance level was set at 0.05. The analysis showed that treatment 4 (4% fiber content, which achieved the highest compressive strength among the mixes with recycled steel can fibers) was not significantly different from the control treatment (treatment 0). Therefore, there was no statistically significant difference between the compressive strengths of these two treatments.

The reduction in compressive strength of fly ash–glass waste FRGC with increasing recycled steel can fiber content is not consistent with findings in the literature regarding the compressive strength of both industrial and recycled fibers. This decrease may be attributed to the aspect ratio of the recycled steel can fibers. Aspect ratio is defined as the length-to-diameter ratio of fibers; for the recycled steel can fibers in this study, it was considered as the length-to-width ratio. These fibers had a relatively low aspect ratio because of their width. Mishra [23] noted that aspect ratio directly affects a fiber’s contribution to the relative strength and toughness of concrete. A higher aspect ratio (i.e., narrower fibers) could have reduced the compressive strength loss or even increased compressive strength, as suggested by Alrawashdeh and Eren [15]. Furthermore, fiber orientation and dispersion within each specimen may also have influenced the compressive strength results [23].

4.3. Split Tensile Strength Test

Similar to the compressive strength test, the data gathered from the split tensile test following ASTM C496 were first evaluated according to ASTM C670. According to ASTM C496 and ASTM C670, the coefficient of variation of three results in a treatment is suggested not to exceed 16.5%. All treatments passed the precision check and were ready for data evaluation.

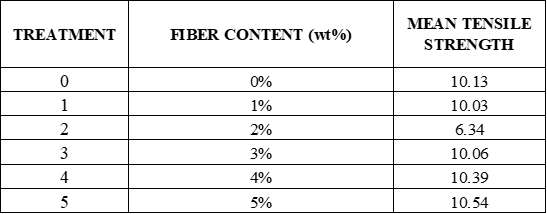

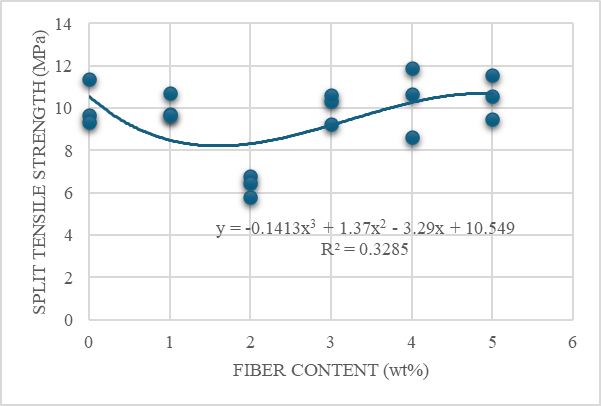

Table 6 shows the mean tensile strength of the treatments at the 28-day curing period. The control group had a mean tensile strength of 10.13 MPa. Figure 5 shows the graph of tensile strength against fiber content, including a cubic regression with an R-squared value of 0.3285. The trend of tensile strength decreased until treatment 2 (2% fiber content), which had the lowest mean tensile strength of 6.34 MPa. The trend then increased with further increases in fiber content. The highest mean tensile strength of 10.54 MPa was recorded in treatment 5 (5% fiber content).

(tensile strength test).

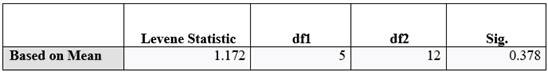

Table 7 shows the homogeneity of variance test for the split tensile strength data. Based on the table, the significance value or p-value is 0.378, indicating no violation of homogeneity of variances. Therefore, only one-way ANOVA was used.

(tensile strength test).

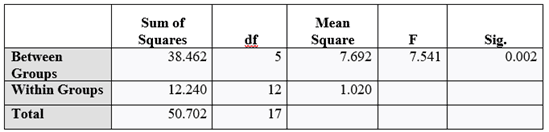

As shown in Table 8, the significance value or p-value is 0.002, which is below the significance level of 0.05. Therefore, there is a significant difference in tensile strength between the fiber content percentages of fly ash–glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers.

A post-hoc Tukey HSD test was used for the split tensile strength data since the groups had homogeneous variances. Based on Table 3.10 of the Tukey HSD test, treatment 2 was the only treatment significantly different from the others. In contrast, treatments 0, 1, 3, 4, and 5 were not significantly different from one another. This means that, despite the increase in split tensile strength recorded as the fiber content in FRGC increased, the increase was statistically insignificant.

The increase in tensile strength of fly ash–glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers, even though insignificant, is consistent with the literature reviewed and the studies of Joshi et al. [13], Alrawashdeh and Eren [15], and Wijatmiko [18]. Similar to compressive strength, a higher aspect ratio could have significantly improved the effectiveness of the recycled fibers in increasing the tensile strength of fly ash–glass waste FRGC [15]. In addition, the insignificant increase in tensile strength may be due to the glass waste decreasing the tensile strength of the concrete treatments, as reported by Malik et al. [20]. Lastly, the orientation of the fibers and how they were dispersed in each specimen may also have contributed to the strength results [23].

4.4. Type of Failure

The ASTM C39 schematic of typical failure patterns was used as reference in determining the compressive strength failure types. For the compressive strength test, most failures observed were type 3: columnar cracking failures, followed by failures with well-formed cones at one end and type 2: vertical cracks running through caps (see Figure 6). One type 2 failure occurred in treatment 0, while another type 2 failure occurred in treatment 4. In addition, the researchers observed a reduction in explosive and loud failures of the concrete cylinders during the test. Many of the fly ash–glass waste FRGC specimens with recycled steel can fibers exhibited silent, ductile failures with reduced concrete spalling.

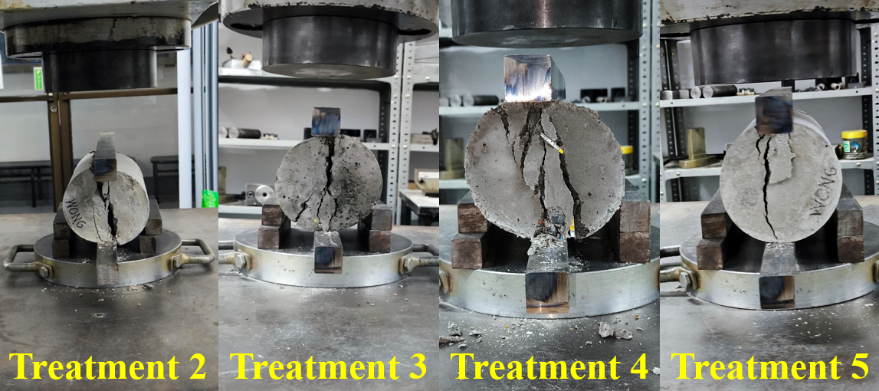

Meanwhile, for the split tensile strength test, the types of failure were classified as follows:

- Type 1 - visible cracks but not end-to-end

- Type 2 - complete separation of the fractured specimen

- Type 3 - hindered fracture of the fractured specimen

(left to right).

A type 2 failure occurred in treatment 0 (see Figure 7). The rest of the specimens in this treatment and treatment 1 experienced type 1 failure. For the succeeding treatments (2–5), type 3 failures were observed (see Figure 8). The specimens that exhibited type 3 failure remained intact after removal from the testing machine (see Figure 9). These phenomena were assumed to occur because of the presence of recycled steel can fibers, which enabled fiber bridging. Moreover, type 3 failures also indicate that ductile failure was achieved in the concrete specimens. A ductile failure provides warning signs of impending failure through visible deformation and allows for remedial action, unlike brittle failure, which occurs suddenly without warning.

The types of failure observed in both the compressive and split tensile tests were consistent with the literature of Jamal [14] and Mishra [23], as well as with the findings of Anas et al. [12], Joshi et al. [13], and Alrawashdeh and Eren [15]. The presence of recycled steel can fibers in fly ash–glass waste FRGC contributed to ductile performance.

5. Conclusion

This study analyzed the mechanical performance of fly ash–glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers. Based on the concrete tests conducted, the workability of FRGC decreased as recycled fibers were added. The study also found that there was a significant difference in the compressive and tensile properties between fiber content percentages of fly ash–glass waste FRGC. Among the treatments, the FRGC with 4% recycled steel can fiber content provided the most desirable results when both compressive and tensile strength tests were considered. Most importantly, the addition of fibers resulted in fiber bridging, which helped the concrete samples resist crack propagation and led to ductile failure.

Although the recycled steel can fibers did not significantly enhance the overall mechanical properties of fly ash–glass waste FRGC, the study underscored the potential of utilizing industrial waste materials to develop more environmentally friendly and sustainable construction materials. The results support the feasibility of integrating recycled fibers into concrete production to reduce waste, minimize environmental impact, and promote sustainable practices in the construction industry. With further research and optimization, this study paves the way for the potential commercial adoption of more sustainable composite materials, contributing to advancements in eco-friendly engineering solutions.

6. Recommendations

Based on the results and findings gathered by the researchers, the following recommendations are offered as possible ways to improve this study:

- Assess the effect of using varying dimensions of fibers (width, length, and aspect ratio) on the workability, compressive, and tensile properties of fly ash –glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers.

Since only one design of recycled steel can fiber was used in this study, it is suggested that future researchers assess the effect of varying fiber dimensions (specifically width, length, and aspect ratio) on the properties of fly ash–glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers. This will provide further knowledge on how the shape of recycled steel can fibers affects the performance of concrete, particularly in terms of aspect ratio, which may have influenced the results of this study.

- Assess the compressive and tensile properties of fly ash–glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers with longer curing periods.

Concrete mixes containing fly ash are known to have delayed strength gain [22]. Furthermore, the glass waste used as coarse aggregate, also acting as a pozzolan, contributes to this delayed strength development [19]. Thus, future researchers are encouraged to assess the mechanical properties of fly ash–glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers over longer curing periods to provide a more accurate evaluation of the concrete’s potential in both compressive and tensile properties.

- Explore analyzing the other mechanical properties, such as flexural strength, modulus of elasticity, shrinkage, and impact resistance, of fly ash–glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers.

It is recommended that future researchers explore additional mechanical properties of fly ash–glass waste FRGC with recycled steel can fibers to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the material, expand the available knowledge, and identify potential improvements for practical applications.

7. Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to acknowledge the funding support provided by Mapúa University and its permission to use university facilities for this study. They also extend their gratitude to Fundamentum Construction and Mr. Jemil Bal for their assistance in producing the recycled fibers. The researchers would like thank the Manila City Material Recovery Facility for supporting the processing of the glass waste. Lastly, they would like to thank Daniel Maranello Wong for helping them proofread this study.

References

[1] S. Chowdhury, R. Ray, and P. S. Ghosh, "Self-healing concrete - a potential sustainable solution for durable concrete structures," TATA Consulting Engineers, Mar. 15, 2023. [Online]. Available: View Article

[2] Hamakareem, "What is reinforced concrete? Uses, benefits, and advantages," The Constructor, Oct. 21, 2019. [Online]. Available: View Article

[3] Anitha, Garg, and Babu, "Experimental study of geopolymer concrete with recycled fine aggregates and alkali activators," Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering, vol. 8, Dec. 2023, Art. no. 100501, doi: 10.1016/j.cscee.2023.100501. Available: View Article

[4] Madhavi, "Geopolymer concrete - the eco-friendly alternate to concrete," NBMCW, May 2020. [Online]. Available: View Article

[5] Afshinnia, "Waste glass in concrete has advantages and disadvantages," Concrete Decor, 2019. [Online]. Available: View Article

[6] REVA University, "Sustainability practices in civil engineering," REVA University. [Online]. Available: View Article

[7] L. Chen et al., "Recent developments on natural fiber concrete: A review of properties, sustainability, applications, barriers, and opportunities," Developments in the Built Environment, vol. 16, p. 100255, Oct. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.dibe.2023.100255. Available: View Article

[8] U.S. EPA, "Containers and packaging: Product-specific data," Nov. 8, 2024. [Online]. Available: View Document

[9] Zone, "Steel cans," Jun. 18, 2019. [Online]. Available: View Article

[10] Mundolatas, "Mechanical properties of cans," MUNDOLATAS, Aug. 11, 2020. [Online]. Available: View Article

[11] ULMA Group, "Steel: Characteristics, properties, and uses," ULMA, Jul. 3, 2023. [Online]. Available: View Article

[12] M. Anas, M. Khan, H. Bilal, S. Jadoon, and M. N. Khan, "Fiber reinforced concrete: A review," Engineering Proceedings, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 3, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.3390/engproc2022022003. Available: View Article

[13] Joshi, Reddy, Kumar, and Hatker, "Experimental work on steel fibre reinforced concrete," International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 971-981, Oct. 2016. [Online]. Available: View Article

[14] Jamal, "Manufacture of steel fibers, properties of steel fibers and their design consideration in RC," Jul. 24, 2017. [Online]. Available: View Article

[15] A. Alrawashdeh and O. Eren, "Mechanical and physical characterisation of steel fibre reinforced self-compacting concrete: Different aspect ratios and volume fractions of fibres," Results in Engineering, vol. 13, p. 100335, Jan. 2022, doi: 10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100335. Available: View Article

[16] Akhund, "Utilization of soft drink tins as fiber reinforcement in concrete," Engineering Science and Technology International Research Journal, vol. 1, pp. 47-52, Jul. 2017.

[17] J. P. Sambrano and Estores, "Optimization of compressive strength of wasted soft drink can fiber non-load bearing concrete hollow blocks," International Journal of Geomate, vol. 22, no. 94, Jun. 2022, doi: 10.21660/2022.94.8. Available: View Article

[18] I. Wijatmiko, "Strength characteristics of wasted soft drinks can as fiber reinforcement in lightweight concrete," International Journal of Geomate, vol. 17, no. 60, Apr. 2019, doi: 10.21660/2019.60.4620. Available: View Article

[19] Tamanna, "Use of waste glass as aggregate and cement replacement in concrete," James Cook University, Apr. 2020. Available: View Article

[20] Malik, Bashir, Ahmed, and Tariq, "Study of concrete involving use of waste glass as partial replacement of fine aggregates," ResearchGate, Jan. 3, 2013. [Online]. Available: View Article Available: View DOI

[21] Adajar, De Mesa, Dizon, Molas, and Quintana, "Assessing the effectiveness of fly-ash in mitigating the alkali-silica reaction in concrete with soda-lime glass," ResearchGate, Jul. 2019. [Online]. Available: View Article

[22] Federal Highway Administration, "Chapter 3 - Fly ash in Portland cement concrete," Federal Highway Administration, 2017. [Online]. Available: View Document

[23] Mishra, "Fiber reinforced concrete - types, properties and advantages of fiber reinforced concrete," The Constructor, 2021. [Online]. Available: View Article