Volume 8 - Year 2025- Pages 01-09

DOI: 10.11159/ijci.2025.020

Experimental Study on Inspector Attributes Influencing Crack Detection in Steel Bridge Visual Inspections

Kouichi Takeya1, Aya Watanabe2, Yuichi Ito3, Eiichi Sasaki1

1Institute of Science Tokyo

2-12-1, Ookayama, Meguro, Tokyo, Japan

takeya.k.aa@m.titech.ac.jp; sasaki.e.ab@m.titech.ac.jp

2Tokyo Institute of Technology (at the time of research)

2-12-1, Ookayama, Meguro, Tokyo, Japan

watanabe.a.at@m.titech.ac.jp

3Institute of Science Tokyo (at the time of research)

2-12-1, Ookayama, Meguro, Tokyo, Japan

ito.y.ca@m.titech.ac.jp

Abstract - Visual inspection is a fundamental approach for maintaining and managing civil infrastructure. However, the qualifications required of inspectors are often ambiguous, which can lead to an oversight of critical defects such as fatigue cracks in steel bridges. In this study, inspectors with varying backgrounds were selected to participate in a simulated visual inspection of an actual steel bridge. Crack detection performance and the identification of atypical structural features were evaluated using eye-tracking measurements and post-inspection interviews. The results indicate that inspectors with technical expertise in fatigue mechanisms were more adept at recognizing structurally vulnerable areas, achieving on average more than five out of seven features compared with fewer than three identified by those without such expertise. However, the difference was not statistically significant due to the limited sample size, suggesting that crack detection rate was not solely determined by experience or technical knowledge. These findings highlight the need for targeted training programs that emphasize typical crack initiation patterns, thereby enhancing the reliability of visual inspections and contributing to more effective bridge maintenance.

Keywords: Visual inspection, Steel bridges, Cracks, Fatigue mechanisms, Eye-tracking, Frame-by-frame analysis.

© Copyright 2025 Authors - This is an Open Access article published under the Creative Commons Attribution License terms. Unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium are permitted, provided the original work is properly cited.

Date Received: 2025-04-10

Date Revised: 2025-10-09

Date Accepted: 2025-10-23

Date Published: 2025-12-03

1. Introduction

Structural deterioration can lead to reduced functionality and an increased risk of failure, emphasizing the need for effective infrastructure maintenance and management practices. Although advanced technologies such as monitoring systems and robotic inspection have increasingly been adopted as alternatives, visual inspection remains a fundamental method for infrastructure maintenance due to its simplicity and reliance on human judgment.

In Japan’s railway sectors, hands-on visual inspections called “general inspections” are performed once every two years for all bridge infrastructure. When defects are identified, the structures undergo additional, detailed “individual inspections” by specialized engineers, including non-destructive measurements [1]. This maintenance management system has been in place for many years. However, if critical defects are missed during the general inspection, they can progress and become more serious before the next round of inspections. In particular, fatigue cracks in steel bridges are a major concern, as even small undetected cracks can rapidly propagate and lead to serious structural damage.

Previous research has shown that even experienced inspectors can fail to detect small fatigue cracks during routine visual inspections, resulting in greater chance of structural risks [2]. Furthermore, factors beyond experience, such as technical understanding and intuitive decision-making informed by tacit knowledge, likely influence inspection accuracy. General inspections involve checking various structural conditions, including corrosion and bearing issues, consequently splitting the inspector’s attention and leading potential oversight of fatigue cracks.

To address this issue and mitigate the limitations of visual inspections, Japan Railway Central has introduced “special inspections” that focus specifically on crack detection [1]. However, the relationship between inspector attribute and crack detection performance remains unclear, adding to the existing key issue of identifying which factors lead to the oversight of fatigue cracks. One challenge is the ambiguity behind required inspector qualifications. For example, although railway maintenance standards [3] state that inspectors should possess appropriate competence in the maintenance and management of structures (translated from Japanese), they do not clearly define what these competences actually entail.

Eye-tracking technology has recently been introduced and proves a promising tool to analyze how inspectors visually engage with tasks, where it has already successfully been used to extract expert knowledge and help understand inspection behavior. For example, Aoshima et al. [4] analyzed inspector gaze patterns during damage evaluation of a concrete bridge, aiming to uncover the influence of intuitive, tacit knowledge. However, few studies have quantitatively examined how an inspector’s technical understanding and experience affects visual attention patterns during the detection of fatigue-related features in steel bridge inspections. Understanding these behavioral differences is essential for improving the effectiveness of inspection training and standardizing inspection quality.

Building upon this gap, this study aims to quantify how the technical understanding and experience of inspectors influence the crack detection rate of visual inspections. A simulated inspection was conducted on an actual steel bridge under the theme of fatigue damage, involving inspectors with diverse backgrounds. By combining eye-tracking data and interview results, the study seeks to clarify underlying differences in detection behavior, reasoning, and inspection performance across different inspector profiles.

2. Methodology and Experiments

This section outlines the experimental method to evaluate the influence of inspector attribute on visual inspection performance.

2. 1. Target Bridge for Inspection

The visual inspection experiment was conducted on a pedestrian bridge located at the entrance of a building in the Institute of Science Tokyo, as shown in Figure 1. The bridge features two welded girders composed of flanges and webs joined by longitudinal fillet welds. While these joints were designed with fatigue category D and defined according to JSSC guidelines (two million cycles, 100 MPa) [6], some other joints fall below this level and are therefore considered vulnerable for road or railway bridge applications. Nonetheless, it is important to note that a lower fatigue category does not inherently indicate weakness as structural vulnerability depends on the balance between the fatigue strength and the actual stress acting on a joint.

This pedestrian bridge was originally designed without specific consideration of fatigue. Due to its structural configuration, both the upper and lower girders are accessible and visible, making it suitable for hands-on visual inspection. The visual inspection experiment was carried out under the assumption that car or train loads pass over the deck slab.

2. 2. Measurement Equipment

Eye-tracking data was recorded using the wearable device (Tobii Pro Glass 2) as shown in Figure 2. This device employs the corneal reflectometry method to detect eye movement and overlays eye marks onto a video recording of the inspector’s visual field. The device also records voice through a built-in microphone. Additionally, two portable cameras were used to record inspector movements with a frame rate of 25 fps.

2. 3. Experimental Setup: Simulated Cracks and Atypical Structural Features

The setup of simulated cracks is summarized in Table 1. The fatigue categories are defined according to the JSSC guidelines [5]. Seven structural joints with high susceptibility to fatigue crack initiation were selected. The simulated fatigue cracks were drawn using a red pencil as shown in Figure 3. In actual bridge inspections, fatigue cracks are often accompanied by coating cracks or rust stains that appear reddish due to corrosion products. The simulated cracks were designed to be 30 mm or longer, representing cracks that have already propagated to a visually detectable stage. This setup focuses on evaluating inspectors’ ability to recognize visible fatigue damage, rather than their capacity to identify microcracks that require magnified inspection techniques.

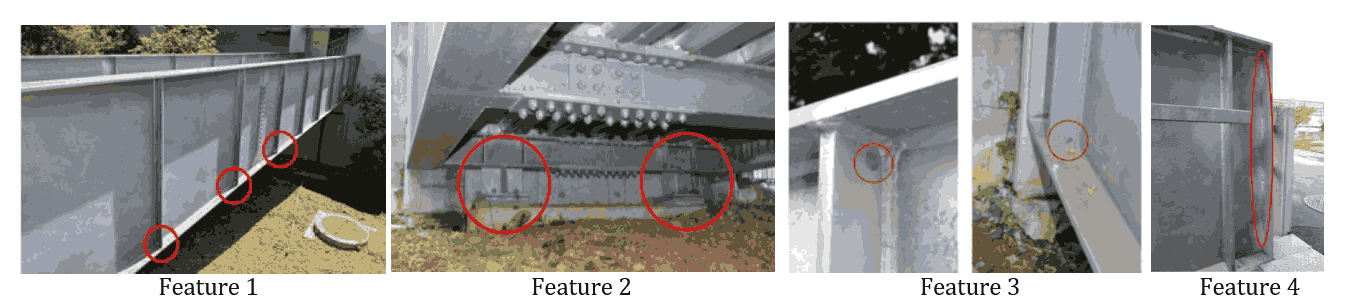

Cracks 4 to 6 were intentionally identical in type to help determine whether inspectors would inspect similar locations after identifying a crack. Crack 7 was added to simulate fatigue in a joint not subjected to external forces, where a steel plate was attached to the lower flange and joined using a silicone-based impression material. Moreover, an inspector’s focus on atypical structural features was analyzed to quantify their understanding of standard road and railway bridge design (Figure 4 and Table 2). The time spent gazing at each point served as an indicator of structural awareness.

2. 4. Analysis Method

Table 1. List of simulated cracks and their locations set on the test bridge.

|

|

Crack location |

Crack length |

Fatigue category [5] |

|

|

Crack 1 |

On-site joint of main girders |

Lower flange horizontal butt weld |

38 mm |

F |

|

Crack 2 |

Web scalloped section |

76 mm |

G |

|

|

Crack 3 |

Joint between the main and horizontal girders |

Lower flange in-plane gusset weld joint |

64 mm |

< H |

|

Crack 4 |

Web out-of-plane gusset weld joint |

73 mm |

< G |

|

|

Crack 5 |

55 mm |

< G |

||

|

Crack 6 |

72 mm |

< G |

||

|

Crack 7 |

Welds of the main girder |

Lower flange attachment |

30 mm |

I |

Table 2. List of atypical structural features evaluated during inspection and their fatigue-related characteristics.

|

|

Structural location or description |

Fatigue category [5] |

|

Feature 1 |

Welding at the bottom end of the intermediate vertical stiffeners |

E |

|

Feature 2 |

Bearing supports transverse girder |

- |

|

Feature 3 |

Scallop-like holes at both top and bottom ends of the intermediate vertical stiffeners |

- |

|

Feature 4 |

Steel plates at girder ends connected by intermittent welds |

- |

|

Feature 5 |

Thickness irregularity of flanges and stiffeners |

- |

|

Feature 6 |

Combined welded and bolted joints in the main girders |

- |

|

Feature 7 |

Welded attachments on the lower flange of the main girders |

I |

2. 4. 1. Detection Rate

The number of detected cracks was evaluated based on whether the inspector explicitly pointed out a simulated fatigue crack. Cracks that were overlooked or not mentioned were categorized as missed detections (false negatives).

Incorrect identifications of cracks (false positives) were not counted in the evaluation. This approach reflects common practice in visual inspections, where suspected damage is typically subjected to further investigation methods such as non-destructive testing. Consequently, such misidentifications do not directly compromise structural safety. In contrast, missed detections (false negative) are regarded as a more serious concern, as they may progress unnoticed and lead to significant damage. Therefore, the detection rate is considered the most important indicator of detection performance in this study.

Where TP (True Positive) denotes the number of correctly detected cracks and (False Negative) represents the number of missed cracks. The same definition and evaluation concept were also applied to the detection of atypical structural features.

2. 4. 2. Gaze Time Analysis

Video data obtained from the eye-tracking device was synchronized with that from the two portable cameras using Adobe Premiere Pro and by aligning timestamps from each device. A frame-by-frame analysis [6] was performed to determine both total inspection time and gazing time for each atypical structural feature. The definition of "gazing" in this study follows typical fixation thresholds used in eye-tracking research, in which fixation is generally considered to occur when the gaze remains on the same location for more than 200 milliseconds [7]. Gaze time was calculated based on the number of frames that the inspector’s eyes remained fixed on each region of interest.

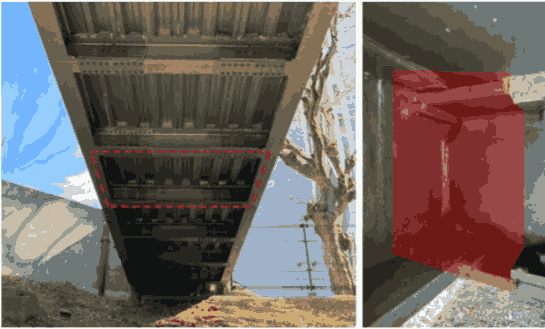

2. 4. 3. Gazing Focus on Weld Lines

To analyze where inspectors focused during weld line inspection, a rectangular frame was defined as shown in Figure 5. Since fatigue cracks are most likely to occur at the start and end of weld lines, the proportion of time spent inspecting these regions was computed relative to the total time spent within their respective rectangular frame. These start/end points were defined as the areas containing in-plane gussets and their surrounding regions. A longer gaze focused on these points was interpreted as a deeper understanding of fatigue-prone areas and more efficient inspection behavior.

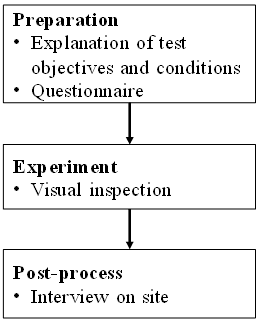

2. 5. Experiment Procedure

The experiment procedure has been summarized in Figure 6. First, a pre-survey was administered to collect background information and classify inspectors according to their experience and expertise. Second, each inspector performed a visual inspection within a maximum time limit of 20 minutes. Soon after the visual inspection, post-experiment interviews were conducted to clarify the intent behind certain gazing behaviors and related crack detection. Based on these interviews, simulated crack detection was categorized according to reasons specified by the inspectors. Likewise, focus on atypical structural features was classified based on perceived discomfort or irregularity.

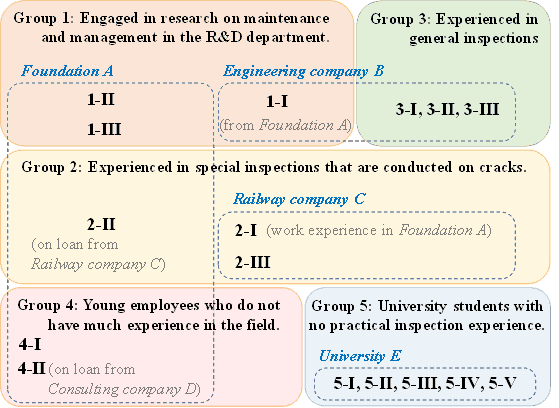

2. 6. Test Inspectors

Prior to the inspection, 15 participants completed a questionnaire regarding both their work and inspection experience. Based on this information, they were classified into five groups as shown in Figure 7. Group 1 consists of three inspectors (1-I, 1-II, 1-III) who have been engaged in research on maintenance and management in a research and development (R&D) institute specializing in railway technology, and who possess extensive experience in the formulation of inspection and design standards. Group 2 consists of three inspectors (2-I, 2-II, 2-III) who possess mainly onsite field experience and more specifically, experience in special inspections of cracks. One of them has been in the R&D department on secondment. Group 3 inspectors are also mainly experienced in the field, but usually perform only general inspections (3-I, 3-II, 3-III). Group 4 consists of two younger employees who do not have much experience in the field: 4-I has some experience in individual inspections where detailed inspections are performed after cracks are found. 4-II only has experience in design and has never performed inspections. Group 5 consists of five university students (5-I to 5-V), including master’s and undergraduate students in civil engineering, with no practical inspection experience.

3. Results

This section presents the results of the simulated visual inspection, focusing on crack detection rate, gaze behavior and inspection characteristics across different inspector groups.

3. 1. Detection of Simulated Cracks and AtypicalStructural Features

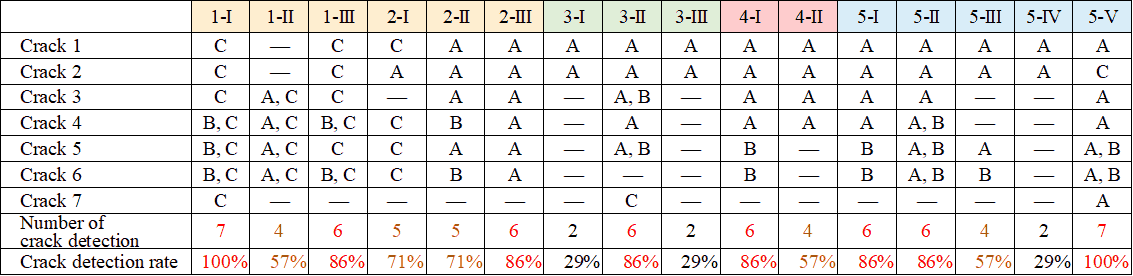

3. 1. 1. Detection of Simulated Cracks

The detection results of the simulated cracks are shown in Table 3. Crack detection was classified into four categories based on the post-experimental interviews: (A) detected by coincidence while looking at weld lines or joints; (B) detected by inspecting similar locations to a previously identified crack; (C) detected while focusing on joints prone to fatigue cracks based on fatigue mechanisms, defined here as the balance between fatigue strength and applied stress.

All three members of Group 1 and one member of Group 2 reported that their findings were based on their understanding of fatigue mechanisms, namely cracks are likely to occur at joints considered fatigue-critical (C). In contrast, many members from the other groups detected cracks either by chance (A) or by inspecting similar locations to a previously detected crack (B). The fact that the detection reasons for all groups besides Group 1 aligned with those of Group 4 and 5, who had little or no inspection experience, suggests that even those with general inspection experience and knowledge do not fully comprehend fatigue mechanisms. This indicates that fatigue cracks can be detected by spending sufficient time on inspecting the entire area, even by inspectors lacking field experience or fatigue-related knowledge, as is the case for Group 5.

Given most inspectors identified fatigue cracks based on reason B indicates that detection rate can be improved by familiarizing inspectors with examples of typical crack initiation points and without their thorough understanding of joint-specific fatigue mechanisms. Furthermore, it is expected that educating inspectors on the fatigue characteristics of each joint will also contribute to more consistent crack detection and consequently more efficient inspection practices.

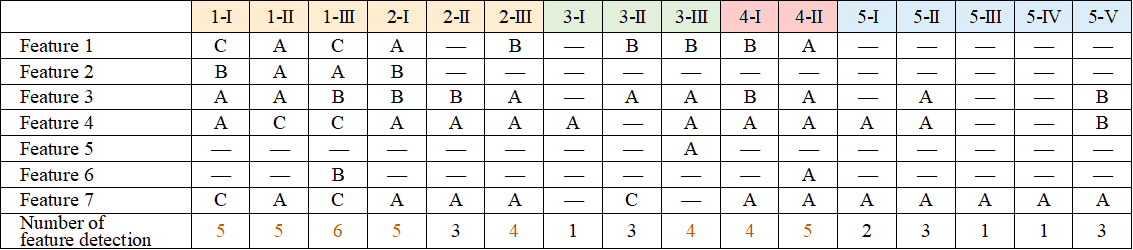

3. 1. 2. Detection of Atypical Structural Features

Table 4 shows the detection results of the atypical structural features. The reasons for focusing on these features were categorized into three types: (A) locations that appeared intuitively abnormal; (B) locations recognized as structurally uncommon or unfamiliar based on individual experience; and (C) locations considered structurally weak from the perspective of fatigue mechanisms.

The number of atypical structural features detected was lowest in Group 5, who lacked practical experience whereas inspectors with practical experience more frequently identified cracks that were uncommon or unfamiliar if based on empirical knowledge. It is therefore evident that identifying potential crack initiation points requires practical experience, including knowledge of actual crack initiation cases. Moreover, inspectors well-versed in fatigue mechanisms, particularly those in Group 1, pointed out a greater number of atypical structural features and their detection was often based not only on intuition but also on fatigue mechanism considerations.

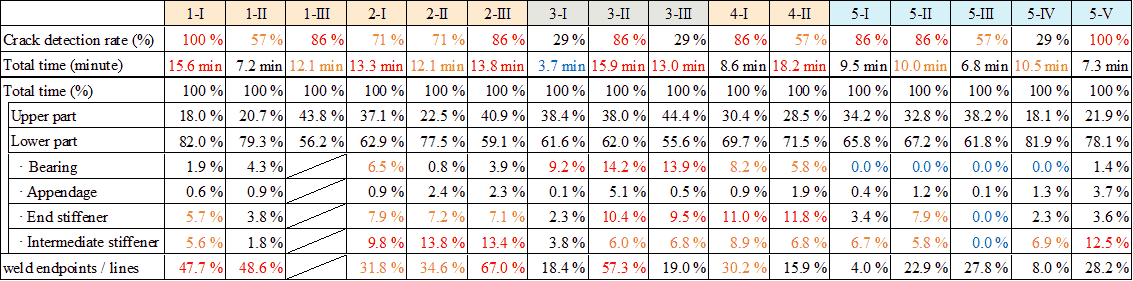

3. 2. Inspection Time

The recorded total inspection time and gaze time for each girder component have been summarized in Table 5. The components included the upper, lower, and side parts of the girder, bearings, post-weld additions, end stiffeners, and intermediate stiffeners. For inspector 1-III, data was incomplete due to device malfunction.

Two main factors that likely contributed to longer inspection times include: (1) revisiting previously observed cracks out of concern of oversight, and (2) perceived pressure from being recorded, despite being informed that performance would not be evaluated.

3. 2. 1. Inspection Time of Upper and Lower Parts

On average, more time was spent on the lower part of the girder with greater focus on bearings and the complex back-side structure, in particularly among the inspectors with field experience. Conversely, Group 3 spent little time on the lower backside and followed their usual practice of focusing on bearings and span ends, which are accessible during general inspections.

3. 2. 2. Atypical Structural Feature 1:

Welds of Lower End of Vertical Stiffeners

Group 2 demonstrated greater focus on intermediate stiffeners, especially their lower ends. These inspections seem to correlate to “special inspections”, which are conducted using scaffolding for closer observation, and have helped foster an awareness of fatigue-prone joints. A notable anomaly is that the weld between the lower end of the intermediate stiffener and the bottom flange, classified as category E (two million cycles, 80 MPa) [5], is considered fatigue-critical in standard fatigue design due to its relatively low strength and location in the bottom flange. This anomaly was noted by all but two inspectors in Groups 1–4, suggesting that those experienced in girder design and inspection could intuitively recognize the risk. In contrast, no one in Group 5 identified this anomaly, indicating the influence of their limited practical experience.

3. 2. 3. Atypical Structural Feature 2: Bearing

Most inspectors in Group 5 did not inspect the bearings, unlike experienced workers, suggesting that bearing inspection may serve as an indicator of practical experience. Group 3 and Group 4 showed greater focus on bearings. Interestingly, although all inspectors besides those in Group 5 inspected the bearings, only four pointed out their unusual placement (Feature 2 in Table 4).

3. 2. 4. Atypical Structural Feature 7:

Welds of Lower Flange Additions

Crack 7 was detected by only inspectors 1-I, 3-II, and 5-V. While inspectors 3-II and 5-V had long gaze times, 1-I was able to detect the crack despite a shorter observation, likely due to their expertise in steel bridge maintenance. Although almost all inspectors pointed out the structural abnormalities of Crack 7 (Feature 7 in Table 4), only three inspectors actually detected the crack. This may be attributed to the relatively faint depiction of the simulated crack.

3. 2. 5. Gazing Point of Weld Lines

The inspectors who gazed the longer at the start and end points were mainly in Group 1 and Group 2. Those who paid less attention to the start and end ends mainly focused on the center of the weld line and the bolted joints.

3. 3. Inspector Characteristics by Individualand Group

3. 3. 1. Characteristics of Individual Inspectors

Inspectors 1-I and 1-III conducted a preliminary survey of both upper and lower parts before beginning a detailed inspection, whereas no one in Groups 2 to 5 took such a comprehensive approach. Inspector 2-I, who achieved results similar to those of Group 1, possessed understanding of fatigue mechanisms and had been previously seconded to an affiliation of Group 1 responsible for developing design and maintenance standards for railway structures. Inspector 5-II, who was an undergraduate student, produced results comparable to those of the senior students. This may be attributed to the fact that civil engineering students have extensive exposure to bridge structures through lectures and coursework. Inspector 3-I and 3-III paid little attention to the backside of the girders and inspector 5-IV paid even less attention to the beginning and end of the weld line.

3. 3. 2. Characteristics of Each Group

Group 1 consisted of inspectors engaged in maintenance-related research and with substantial experience in fatigue mechanisms and inspection criteria. They detected both the simulated cracks and the atypical structural features, often citing fatigue mechanisms as the reason. Their inspection process was also characterized by an initial effort to comprehend the overall structure before examining individual components in greater detail.

Group 2 showed inspection behaviors similar to that of Group 1, particularly in their detailed observations of intermediate vertical stiffeners and other components. This can be attributed to their experience with “special inspections”. However, unlike Group 1, their detections were based more on prior experience with crack initiation than a technical understanding of fatigue mechanisms. Inspectors with backgrounds similar to Group 1 tended to achieve comparable results.

Group 3 was experienced in regular “overall inspections” and tended to focus on bearings and end stiffeners while spending less time inspecting the lower backside of the girder. Their inspection style reflected an efficiency-oriented approach. Two members in this group detected the lowest number of simulated cracks, partly due to insufficient attention to the lower back surface.

Group 4 comprised younger members with little field experience, and exhibited inspection behavior patterns similar to Group 5. However, they were able to point out specific fatigue-prone features, such as the lower end of the intermediate vertical stiffener, possibly due to practical exposure to bridge structures.

Group 5 consisted of students without any prior inspection experience. Nevertheless, they were able to detect simulated cracks efficiently, primarily by inspecting welds. However, they did not focus on bearings and failed to identify most atypical structural features, reflecting the limitations of their inexperience.

4. Conclusion

This study experimentally investigated the influence of inspector background and experience on the performance of visual inspections for fatigue cracks in steel bridges. Simulated visual inspection was conducted on an actual steel bridge, with results analyzed through eye-tracking data and post-inspection interviews.

Fatigue cracks were often detected accurately, even by inspectors lacking direct inspection experience or knowledge of fatigue mechanisms. However, many cracks were detected either by chance or by pattern-based searching rather than through technical understanding of fatigue behavior. The fact that multiple inspectors detected simulated cracks using pattern-based searching suggests that familiarizing inspectors with examples of typical crack initiation locations can improve detection rate, even in the absence of in-depth structural understanding.

Inspectors without practical field experience had difficulty identifying atypical structural features, detecting on average fewer than three out of seven features. In contrast, those with expertise in fatigue mechanisms recognized more than five features on average, demonstrating a broader awareness of fatigue-prone details. This trend highlights how technical knowledge can improve the identification of structurally vulnerable locations. However, the difference was not statistically significant due to the limited sample size, indicating that neither knowledge of fatigue mechanisms nor field experience alone can be regarded as a decisive factor in improving crack detection rate. These findings suggest that while fatigue-specific knowledge is crucial for locating potential weak points, improving actual crack detection requires additional strategies, such as targeted training covering typical crack patterns and inspection techniques.

In addition, the study highlights the importance of integrating both experiential knowledge and technical expertise into inspection practices and training curricula. The relatively small sample size and the use of a simulated inspection environment are limitations, and future work should extend the analysis to larger and more diverse inspector populations. Further research should also examine the potential for combining visual inspection with emerging non-destructive evaluation and monitoring technologies. Such efforts will contribute to establishing more reliable and adaptive bridge maintenance management systems aligned with inspector qualifications.

References

[1] M. Seki, "Large-scale Renovations of the Civil Engineering Structures along the Tokaido Shinkansen," Japan Railway & Transport Review, no. 62, pp. 16-31, 2013.

[2] D. M. Frangopol, M. Soliman, and C. P. Ellingwood, Quantifying the Value of Structural Health Monitoring for Life-Cycle Management of Civil Infrastructure, Purdue University, Joint Transportation Research Program, Publication FHWA/IN/JTRP, 2013.

[3] Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Technical Regulatory Standards on Japanese Railways, 2007.

[4] K. Aoshima, H. Tamai, Y. Noma, Y. Higuchi, K. Fukawa, Y. Yamaguchi, Y. Yamada, D. Yoshimoto, K. Eguchi, and Y. Oshima, "A study on extracting tacit knowledge for bridge soundness diagnosis using line-of-sight information," Artif. Intell. Data Sci., J2-3, pp. 650-660, 2022.

[5] Japanese Society of Steel Construction, Fatigue Design Guidelines for Steel Structures, 2012.

[6] Y. Takeo, "Experimental study on change in gaze point with the proficiency in monozukuri skills," Bull. Human Resour. Dev., vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 1-8, 2014.

[7] D. D. Salvucci and J. H. Goldberg, "Identifying fixations and saccades in eye-tracking protocols," in Proc. Symp. Eye Tracking Res. Appl., pp. 71-78, 2000. View Article